Among Winter Cranes

“Even as birds that winter on the Nile…” (Purgatorio XXIV.64)

The Quarterly of the Christian Poetics Initiative | Vol. 8 Issue 4 | Autumn 2025

Watching Plants Die: Lilias Trotter's Parables of the Cross and Attending to the Dying Process of Plants

by Celia Jarvis-Stalin

Celia Jarvis-Stalin is a final-year doctoral student working on Christian mysticism and the works of artist and missionary Lilias Trotter in a PhD entitled 'Lilias Trotter and the Christian Mystic Visionary: Ways of Seeing'. She studies her PhD in a co-tutelle between The University of Warwick in the UK, and the Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour, France.

The three tomato plants we planted at the end of the summer look sad. They are all limp and clinging to the props we put in their pots. I’ve watched the stems shrivel and fade from pale green to pale straw. In all honesty, I’m not sure they ever looked happy.

We live in Brittany, North-West France and we planted them just at the point where summer suddenly decided to take its leave. We harvested one tomato, and even that had black mildew on it. They were cuttings from a family member, and we gladly accepted. We failed. They’re dying.

It is an interesting experience to receive a plant, and to pot it at the moment you know it is dying and probably won’t come back. This experience has led me to all sorts of questions about the value of living plants versus dying and dead ones, and the value I place in the living ones in my house purely for aesthetic reasons. Are plants really meant to be looked at?

In the last edition of Among Winter Cranes, Holly Spofford-McReynolds wrote that in attending to all aspects of nature, including those less evidently beautiful (such as the wasp, or the cold floppy fish), ‘we avoid pretending that the nature we encounter each day is all sunshine, daisies, and skylarks. This protects us from one ethical issue—lying about what nature is—that arises in attending to nature.’ She discussed the dangers of how this lying to ourselves about nature can also be something we use to minimize those aspects of the nature of God that we find uncomfortable, ‘disconcerting’ or less appealing to our individual sensibilities.1 Lilias Trotter deals exactly with the unloveliness of nature and the unsettling aspects of God in her work.

Lilias Trotter, missionary, painter, writer, and friend of John Ruskin, wrote, painted and paid attention to botanical life in all seasons of its life cycle. In her 1895 devotional parable book the Parables of the Cross of which the epigraph reads, "Mors Janua Vitae” (death is the gateway to life), Trotter leans into the lessons a Christian can gain from the death and decay of plants through writing and watercolour sketches. She talks about death being 'the gate of life’ and a gate that Christians come to ‘again and again, as our lives unfold,’ adding that the life we come to ‘each time is more abundant, for each time the dying is a deeper dying.’2

In this paper, I lay out some of the lessons I have learned alongside Trotter as I prepare to write a chapter on Trotter’s mystical vision of plant life. I take examples from her text and watercolours to trace out the symbolic posture of contemplative prayer and surrender that she reads in the life cycle of the plants. I start with the question Trotter poses to her Christian reader at the beginning of the Parables of the Cross, one that establishes the context in which she asks us to engage with her work:

Have we learnt to go down, once and again, into its [death’s] gathering shadows in quietness and confidence, knowing there is a “better resurrection” beyond?3

In the phrasing 'to go down’ we see the involvement required to read and approach Trotter's text—it requires a posture of the heart and an effort of the imagination to enter into death’s ‘gathering shadows’. It is most likely that the “better resurrection” that Trotter cites refers to Christina Rossetti's poem of the same name in which Rossetti uses the image of the heart of stone, a faded leaf and a broken bowl to describe her inner spiritual life:

I have no wit, no words, no tears;

My heart within me like a stone

Is numb'd too much for hopes or fears;

Look right, look left, I dwell alone;

I lift mine eyes, but dimm'd with grief

No everlasting hills I see;

My life is in the falling leaf:

O Jesus, quicken me.

My life is like a faded leaf,

My harvest dwindled to a husk:

Truly my life is void and brief

And tedious in the barren dusk;

My life is like a frozen thing,

No bud nor greenness can I see:

Yet rise it shall—the sap of Spring;

O Jesus, rise in me.

My life is like a broken bowl,

A broken bowl that cannot hold

One drop of water for my soul

Or cordial in the searching cold;

Cast in the fire the perish'd thing;

Melt and remould it, till it be

A royal cup for Him, my King:

O Jesus, drink of me.4

At the end of each verse Rossetti responds to the image of stone, leaf or bowl, with a prayer, ‘O Jesus, quicken me…O Jesus, rise in me…O Jesus, drink of me.’ From within the same voice with which she laments her ‘husk, void, broken’ life, a prayer wells up asking Jesus to ‘quicken, rise’ and eventually ‘to drink’ of her. Rossetti holds the dichotomy of emptiness with the assurance of knowing it will be filled. It is as if in each verse, Rossetti holds forth the stone, the leaf, the bowl in expectancy that they will be transformed. We see Trotter employing this style too in the pattern of holding forth the ‘barrenness of our souls’ and expecting ‘God’s quickening breath’ to come and restore and revive.5

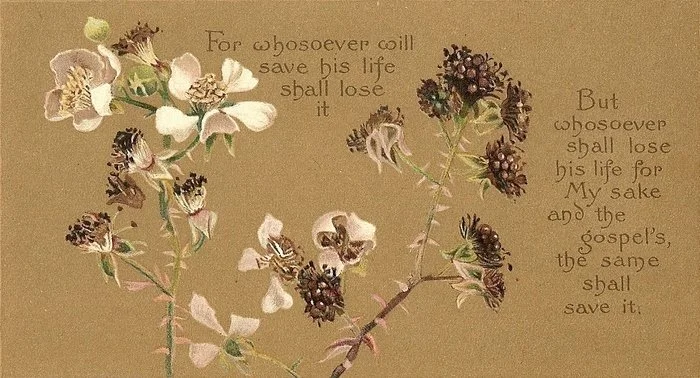

Figure 1. Parables of the Cross, ‘Death to lawful things is the way out into a life of surrender.’

Figure one from the Parables of the Cross, is a watercolour sketch placed in the middle of a section of text entitled Death to lawful things is the way out into a life of surrender. In this image, Trotter puts the beginning of Jesus’ words from Matthew 16:25 ‘whosoever shall save his life shall lose it’ next to the blooming plant. Next to the dead plant she writes: ‘But whoever shall lose his life for my sake and for the gospel shall save it.’ In this curated arrangement of biblical text set alongside the two examples of the blooming plant and the dying one, we learn that aestheticism is not the chief end of Trotter's painting. Though the blooming flower may be desirable, appealing and worthy of beholding, its counterpart—the dying stem—is what is truly worth looking at.

This lesson has come to me: the lesson of death in its delivering power. It has come as no mere far-fetched imagery, but as one of the many voices in which God speaks, bringing strength and gladness from His Holy Place.6

In the illustration the water colour palette is not suggestive of nature’s vivace spring and summer hues; instead it is earthy, mulch-like and decayed. All across Trotter’s work, darker tones are associated with the inner life of spiritual being, and tell of how Trotter visualises sanctification as a process poetically hidden within the earth, just as in Psalm 139 “My frame was not hidden from you, when I was being made in secret, intricately woven in the depths of the earth.”7 In her text, Trotter is reverent of the secrecy of the dying process she is painting, especially of the metaphor it plays of the intimate dying a Christian goes through in the inner life. She writes: ‘We may and must, like the plants, bear its marks, but they should be visible to God rather than to man.’8 In terms of how practically to enter into this state of dying, Trotter proffers that obedience is a way of being able to die from what is ‘lawful’.

The one thing is to keep obedient in spirit, then you will be ready to let the flower-time pass if He bids you, when the sun of His love has worked some more ripening. You will feel by then that to try to keep the withering blossoms would be to cramp and ruin your soul. It is loss to keep when God says 'give'.

For here again death is the gate of life: it is an entering in, not a going forth only; it means a liberating of new powers as the former treasures float away like the dying petals.9

In the first sentence of this passage, Trotter suggests ‘obedience in spirit’ as the fuel for waiting out the transformative experience she describes. Her voice is prophetic as she reassures her reader in phrases like, ‘then you will be ready…you will feel by then…’.

The experience she describes is meditative, and infers that her reader, by taking on obedience, also will play the role of the plant in this passage, waiting to be ripened by the ‘sun of His love’ (and of course, we read here, the Son of His love). The lesson is that the reader must choose to be present within the presence of the sun. This makes sense, when we think that, as we bask in the sun on a warm day, we are present in its rays, but beyond that, we are in its presence, it is doing the basking to us. The lesson here is that being attentive to nature means allowing it to be attentive to you.

I go among trees and sit still.

All my stirring becomes quiet

around me like circles on water.

My tasks lie in their places

where I left them, asleep like cattle.

Then what is afraid of me comes

and lives a while in my sight.

What it fears in me leaves me,

and the fear of me leaves it.

It sings, and I hear its song.

Then what I am afraid of comes.

I live for a while in its sight.

What I fear in it leaves it,

and the fear of it leaves me.

It sings, and I hear its song.10

In Wendell Berry’s poem above, being attentive is transactional as well as transformative. The creature he fears ‘lives a while in my sight’ before the perspective is switched and it is he that ‘lives a while’ in the creature’s sight. At the beginning of Berry’s poem, he ‘goes and sits’ among the trees. There is purpose in the action that leads to the meditative state both he and the creature enter. Reading Berry brings up the word ‘assiduity’ for me, particularly its French equivalent l’assiduité, which finds its etymology in the idea of 'sitting down' and being ‘present’ in a place. If we take both the French and English meaning, of paying close and diligent attention and of ‘sitting down,’ we find something that starts to resemble prayer.

In Merold Westphal’s Prayer as the Posture of the Decentred Self, God's presence is perceived as always having been, and that prayer requires the posture of presenting oneself into that presence. Jean Louis Chrétien defines prayer as ‘‘the speech act by which the man praying stands in the presence of a being in which he believes but does not see and manifests himself to it…The first function speech performs in prayer is therefore a self manifestation before the invisible other.”11

After days of labor,

mute in my consternations,

I hear my song at last,

and I sing it. As we sing,

the day turns, the trees move.12

Perhaps we could replace the 'speech act' of Chrétien's definition, with the 'going and sitting' of Berry or the 'keeping obedient in the spirit' of Trotter as the beginning posture to prayer. In Berry's poem the creature is nameless and formless (to us) but, in the culminating verse of Berry's poem, after having been present to the creature and in the presence of it, he eventually hears his own (prayer?) song. For Trotter, the outcome of this prayer posture is not a song, but is 'surrender.'

This posture of contemplative prayer is just like Trotter's flower. As the Christian takes on the role of the dying flower in Trotter’s text, they (mentally) sit down, they become assiduous, and then they enter into a state of meditative prayer, where they wait on the sun/Son to transform and ripen the petals they cling onto. Trotter says that the petals represent ‘lawful things.’ It is because this new ‘deeper dying’ is not about the first conversion experience of dying from an old way of living into a new Christian life. Instead, she speaks to the tendency of the already Christian to be like the Pharisee who clings onto the law of the old covenant and to his perceived idea about the way in which he thinks he is supposed to live as a Christian rather than on the way Jesus calls him to live.

Moreover, the position of the flower, both actively and passively meditating as a form of prayer, allows the Christian to feel phenomenologically what it must be like for the flowerhead in figure one to hold onto the withering blossoms that ‘cramp and ruin the soul.’ The word ‘cramp’ takes on an embodied reality. The muscle memory thinks about what it is like to hold on tightly, and the Christian feels the discomfort in their hand. Trotter makes us live the physical reality of the flower as a symbol of the psychological pain of clinging onto the life-draining law. And alas, when the Christian finally lets go of their metaphorical petals, they, according to Trotter, do not feel the pain of death at all.

We cannot feel a consciousness of death: the words are a contradiction in terms. If we had literally passed out of this world into the next we should not feel dead, we should only be conscious of a new wonderful life beating within us.13

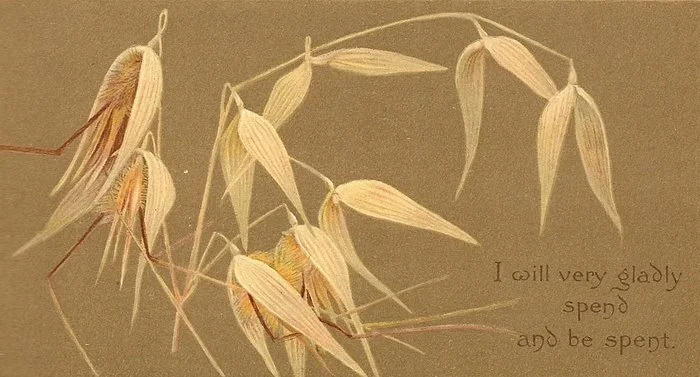

It is a further reassurance for the Christian that chooses to adopt the role of the dying plant, that though they chose to die to the self, they will not feel the emotional, physical, spiritual death, only the petalled-flower representing the holding on to former treasures will feel the physical cramp and ruin of continuing in the former life. Instead, the surrendering that the Christian/plant adopts creates space for a new life of ‘surrender’. James R. Mensch in Prayer as Kenosis makes the case for prayer as an act of Kenosis, wherein, like Jesus, the believer empties themselves out, so that God can come dwell within the believer. Mensch says that in praying this way, we become the ‘nurturing space that is receptive to the ‘‘let there be’’ of the action of this love.’14 Trotter calls this ‘let there be’ the ‘life of sacrifice’ which she illustrates in the watercolour of the oat-grass (Figure two).

See how this bit of oat grass is emptying itself out. Look at the wide - openness with which the seed-sheaths loose all they have to yield, and then the patient content with which they fold their hands - the content of finished work.15

Figure 2. Parables of the Cross, ‘Death to self is a way out into a life of sacrifice.’

Figure 3. Parables of the Cross, ‘Death to self is a way out into a life of sacrifice.’

Again in this passage we see that Trotter personifies the Oat-grass with the folding of the hands. This is an example of a plant that has already yielded all it has to yield, this time not to the sun/Son, but to the ‘wind’ the - Holy Spirit which ‘shakes forth the last seed’ allowing the plant to die contented. For Trotter though, the death of the plant is never truly the end of the plant’s life, nor the Christian’s spiritual life, as Figure three illustrates. The lesson is to be learned in the full cycle of dying and living, for which Trotter paints and writes:

Life leads on to new death, and new death back to life again. Over and over when we think we know our lesson, we find ourselves beginning another round of God's Divine spiral: "in deaths oft" is the measure of our growth, "always delivered unto death for Jesus' sake, that the life also of Jesus might be made manifest in our mortal flesh."16

In Figure four, Trotter captures the ‘glory’ of the arrival of a soul which God has ‘brought into blossom’ through the metaphor of the gorse-bush. Trotter seems to be acutely aware of, and sympathetic to the lived experience of the plant. She bears witness to not only the intensive process of a plant dying but also to the difficulty of flowering in spring time, concentrating all its energy to bloom despite the thorns it may carry. After a conversation recently with a loved one, I reflected on the subtle differences between the verb ‘to bloom’ and the French equivalent ‘s’épanouir.' The loved one told me, ‘tu t’épanouis’ (you are blooming), and I felt the holistic weight of that word spoken by someone who has attended to the whole process of blooming. The verb ‘s’épanouir' in that sentence gave space to both the difficulty and effort of coming out of the bud, and to the radiance of finally wearing a blossoming flower crown.

See this bit of gorse-bush. The whole year round the thorn has been hardening and sharpening. Spring comes: the thorn does not drop off, and it does not soften; there it is, as uncompromising as ever; but half-way up appear two brown furry balls, mere specks at first, that break at last—straight out of last year's thorn—into a blaze of fragrant golden glory.17

Figure 4. Parables of the Cross, 'Death to Sin is the Way out into a life of holiness.'

In the text which surrounds Figure four, Trotter calls us to ‘see this bit of gorse-bush.’ The ‘bit of’ suggesting at first that it is insignificant and small in size. but which she wholly contrasts in the watercolour on the next page of the vivacious blossoming gorse-bush. The ‘hardening, sharpening’ and ‘uncompromising as ever’ nature of the gorse-bush in the text is contrasted with the ‘blaze of fragrant golden glory’ captured in the rich golden yellow of the petals against the vivid deep green of the thorns as alive as the petal head. It is as if, in her watercolour, Trotter captures the sigh of the ‘at last’ that we hear in her voice as she captures the ‘glory’ of the blazing flower sprawled across the page. Even the verse she has chosen to accompany the image ‘setteth in pain the jewel of His joy’ seems to sigh in the background as we observe in the cascading placement of the text the distillation of the setting in ‘pain’ into one simple word ‘joy’. This is accompanied in the text with an exhortation from Trotter:

Take the very hardest thing in your life—the place of difficulty, outward or inward, and expect God to triumph gloriously in that very spot. Just there He can bring your soul into blossom!18

After 'seeing’ the triumph of the gorse-bush, Trotter asks her reader to ‘take,’ again with a phenomenological implication of physically taking hold of the thing in their hand that is the hardest in their life. In this instance, the meditative waiting that we saw in the first lesson of figure one—passively waiting for the sun to ripen, becomes an active holding up the thing that hurts into the Son. In the process of blooming, the plant must move, it must take up action, and Trotter’s impetus is that we too must take that hardest thing and wait with it expectantly in the presence of God.

Two days ago when I passed by the tomato plants, I saw out of the corner of my eye one of the three which seemed to be, (I hesitate to say ‘flourishing’ because that wouldn’t be true) in the process of reviving. I can't say like Lilias Trotter that the tomato plant spoke to me with God’s voice, but I can say that in witnessing this somewhat revival, I was reminded of the words of the psalmist David in Psalm 145.

The LORD upholds all who are falling

and raises up all who are bowed down.19

Anytime I think of this psalm, I can’t help but think of the image of the drooping Dahlias from the poem Unfinished, written by the poet Halle Thomspon living in Brittany, France, which reads:

I read that dahlias may droop

in times of stress—

Who doesn't when faced with the

unfinished poems of our lives?

But the secret of their sagging

stems is this:

water sent from leaves

to strengthen roots.

[...]

Meet me in the greenhouse,

warmed by sunlight,

where a tender gardener

will write the lines to come...20

Reading this psalm and this poem in conversation with Rossetti and Trotter’s work I can’t help but picture those from Psalm 145 ‘who are falling’ as Rossetti’s falling faded leaf21 or as Thompson’s drooping dahlias22 or as Trotter’s surrendering oat-grass.23 The point is that these writers remind us in attending to the death process of a plant, that there is always in the dying, the drooping, the fading and the falling, a deeper hope and the immanent possibility for new life to come.

Furthermore, as we have seen, for Lilias Trotter, watching plants die teaches the Christian how to posture the heart like a flower in prayer, whether that is in meditatively waiting for the sun/Son to ripen you, kenotically allowing oneself to be emptied out like the oat-grass or by actively taking hold of painful things and expecting the Lord to bring joy and transformation amongst the thorns of the gorse-bush. Essentially, by adopting these prayer postures, the Christian reading Trotter’s work is guided through the death process of sanctification as a flower goes through its perennial lifecycle. And the Christian learns that all throughout the dying process, there was the grace of a ‘tender gardener’24 and more importantly still, the Christian undergoing this dying process will eventually see that it was never really about death at all, but about the full, abundant life that Jesus offers to all in the gospel:

I came that they may have life and have it abundantly. 25

Celia Jarvis-Stalin

Cotutelle PhD Student at Université de Pau et des Pays de l'Adour, France and The University of Warwick, UK.

celia.jarvis@univ-pau.fr

All figures are taken from Lilias Trotter’s Parables of the Cross and are open access online through Project Gutenberg. Accessed 30 September 2025. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22189/22189-h/22189-h.htm

1 Holly Spofford-McReynolds, ‘Nature Lovely and Unlovely,’ Among Winter Cranes 8, no. 3 (2025): 8-9. https://www.thercta.org/awc/archive/vol-8-issue-3-spofford-mcreynolds.

2 Lilias Trotter IL, Parables of the Cross (Project Gutenberg), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22189/22189-h/22189-h.htm.

3 Trotter IL, Parables of the Cross.

4 Christina Rossetti, ‘A Better Resurrection.’ The Poetry Foundation. Accessed 30 September 2025. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44991/a-better-resurrection.

5 Trotter IL, Parables of the Cross.

6 Ibid.

7 Psalm 139:15 (English Standard Version)

8 Trotter IL, Parables of the Cross.

9 Ibid.

10 Wendell Berry, ‘I Go Among Trees And Sit Still.’ In This Day: Collected & New Sabbath Poems (Counterpoint Berkeley, 2014), 7.

11 Jean-Louis Chrétien cited by Merold Westphall in The Phenomenology of Prayer, ed. Bruce Ellis Benson and Norman Wirzba (Fordham University Press, 2005), 22.

12 Wendell Berry, ‘I Go Among Trees And Sit Still’, 7.

13 Trotter IL, Parables of the Cross.

14 James R. Mensch, ‘Prayer as Kenosis’ in The Phenomenology of Prayer, ed. Bruce Ellis Benson and Norman Wirzba (Fordham University Press, 2005), 72.

15 Trotter IL, Parables of the Cross.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Psalm 145:14

20 Halle Thompson, ‘Unfinished.’ Grace Reflected. Accessed 1 October 2025. https://hallethompson.blogspot.com.

21 Rossetti, ‘A Better Resurrection.’

22 Thompson, ‘Unfinished.’

23 Trotter IL, Parables of the Cross. (See Figure 2)

24 Trotter IL, Parables of the Cross.

25 John 10:10

Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library. “Momoyogusa = Flowers of a Hundred Generations.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1909. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-cb13-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Dante Aligheri. The Divine Comedy: Purgatorio. Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. New York: Bantam Dell, 2004.